Guest Blog: The History of Cleft in Literature

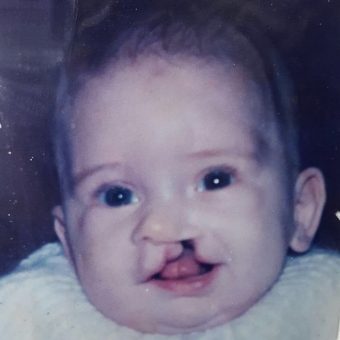

Laura Kennedy was born with a complete unilateral cleft lip and palate in 1984. Her repairs were completed at Alder Hey Hospital, with further treatment at the Royal Liverpool Dental Hospital.

Laura has always worked in education, completing a PhD at Loughborough University in 2013, which examined oral health in the early modern period and included a chapter focused on the history of cleft lip and palate. She is currently working as an Employability Officer at the University of Liverpool.

Laura is keen to raise awareness of the cultural history surrounding facial clefts, and if anybody would like to get in touch to chat about her research, you are welcome to email her at [email protected].

The History of Cleft in Literature

Growing up with the scar from my unilateral cleft lip and palate repair, I was always aware that some people called the condition ‘harelip’, or sometimes spelt ‘hairlip’. I guessed that this was because of the appearance of the scar on my top lip.

When I was in the final year of my English degree at Loughborough University in 2005, I started to get interested in how clefts and other facial differences were written about in literature, and so I completed my undergraduate dissertation on the representation of facial clefts in 20th century literature.

One of the first things I wanted to find out was the origin of the term ‘harelip’. Oxford Reference suggests the term was coined by Roman Greek Physician Galen who lived between 129-216AD. In Greek, it was called ‘lagocheilos’ which translates quite literally as harelip.

The Oxford English Dictionary has details of a written reference to ‘harelip’ in 1567 in a document produced by Thomas Harman called ‘A Caveat or Warning for Common Cursitors (Vulgarly Called Vagabonds)’, which promised to unveil to the reader the criminal underworld in the South of England. Counted amongst a list of ‘Palliards’ (a professional beggar or vagabond) is a man called ‘Wylliam Coper with the harelyp’. It might also be worth noting here that archaeological evidence suggests that it would have been unusual for babies born with cleft palates to survive into adulthood, due to the first successful palate repair not being until 1816, suggesting Wylliam Coper had an isolated cleft lip.

It didn’t take long when researching the word ‘harelip’ to discover that it’s often been assumed that the term was given because of the similarity in appearance to a hare’s cloven top lip, but there is perhaps more to it than this. The potential power of the maternal imagination is often written about in medical texts in the early modern period. In Jane Sharp’s The Art of Midwifery (1671) she describes how ‘suddain fears, for many a woman brings forth a Child with a hare lip, being suddenly frighted when she conceived by the starting of a Hare, or by longing after a piece of a Hare’. This outlines the belief that if a pregnant woman was startled by a hare crossing her path when she was pregnant or craved hare meat, she would give birth to a child with a cleft. This is often written about, but it is impossible to say whether this belief was commonly held as true.

Once I was happy I had an understanding of how clefts were referred to throughout history, I trawled through online databases in pursuit of books, plays or poetry which featured a character with a cleft, or referenced the condition in another way. Shakespeare himself references the ‘harelip’ twice in his plays. Once in A Midsummer Night’s Dream:

“So shall all the couples three

Ever true in loving be,

And the blots of nature’s hand

Shall not in their issue stand.

Never mole, harelip, nor scar,

Nor mark prodigious such as are

Despisèd in nativity

Shall upon their children be.”

And in King Lear:

“This is the foul fiend Flibbertigibbet. He begins at curfew and walks till the first cock. He gives the web and the pin, squints the eye and makes the harelip, mildews the white wheat and hurts the poor creature of the earth.”

I ended up with a list of nearly twenty works of literature that either contained a character with a cleft or referenced the condition. Knowing I only had 8000 words to fill, I had to narrow the selection down, but make sure that I referred to as many texts as possible. I decided to focus on Precious Bane by Mary Webb (1924), A Gun for Sale by Graham Greene (1936), and Red Dragon by Thomas Harris (1981).

Unfortunately, A Gun for Sale and Red Dragon are well-entrenched in the age-old idea that scars equal villains. A Gun for Sale’s Raven is treated slightly more sympathetically, as Greene explores the idea that his criminal ways might be partly the result of him being treated as an outsider, but in Red Dragon, as you’d expect, Thomas Harris goes for all-out horror and the cleft scarring is exploited as part of that.

It was interesting to see that the earliest representation of a character with a cleft was actually the most progressive and compassionate. The protagonist of Precious Bane is an extraordinary woman. She endures with unending patience the strange things people say to her about her appearance: “For she always thought, in common with many people, that if there was anything wrong with a person’s outward seeming, there must be summat wrong with their mind as well.” If you are thinking about reading a book featuring a character with a cleft, make it this one; you won’t regret it.

It wasn’t always easy reading some of the depictions of clefts, but I did feel as though it helped me to reassure myself how ridiculous it was to be so obsessed with appearance. Being somebody who always looked different to my friends and who had to undergo a lot of medical intervention, I found it really heartening to find a heroine in Prue Sarn, written nearly a hundred years ago, whose self-worth is rooted firmly in her internal character, so much so her unrepaired cleft feels much more like everybody else’s issue, rather than hers. She says: “But when you dwell in a house you mislike, you will look out of a window a deal more than those that are content with their dwelling.”

I absolutely loved writing my undergraduate dissertation and reading all of the books I’d found with characters with clefts. In fact, it led me to complete my PhD thesis on oral health in the early modern period, including a chapter on the history of clefts. When I had the idea for the research, I wasn’t sure if it would be considered too niche, but it was soon apparent that a lot of the themes surrounding facial difference, beauty ideals, scarring and birth defects are completely relevant to our appearance-obsessed society.

If anybody would like to get in touch with me about my research, please feel free to email me at [email protected].